and why you should consider the DIGISOC master…

What does a dispute over Greenland have to do with your hospital appointment, your unemployment benefits, or your ability to register a vehicle? More than you might think. Recent geopolitical tensions between the United States and Europe have exposed a vulnerability that runs deeper than trade tariffs: Europe’s critical digital infrastructure is overwhelmingly dependent on American cloud providers.

The numbers behind the dependency

US cloud providers (Amazon Web Services, Microsoft Azure, and Google Cloud) control approximately 70% of Europe’s cloud market. European providers hold just 15%, down from 27% in 2017. A European Parliament report on technological sovereignty estimates that the EU relies on non-EU countries for over 80% of digital products, services, infrastructure, and intellectual property. This isn’t merely a market share statistic. It represents a fundamental vulnerability that intersects technology, law, policy, economics, and geopolitics.

Dutch technology expert Bert Hubert recently published a ‘dashboard of American dependencies‘ that maps which critical Dutch services run on US cloud infrastructure. The findings are striking: UWV (unemployment benefits), welfare payments for major cities, all 100 Dutch municipalities, the judiciary, vehicle registration (RDW), and significant parts of the tax authority all depend on Microsoft Azure or other US cloud services. In healthcare, many hospital workplaces are virtualized to American data centers. The system handling all medical referrals (ZorgDomein) runs entirely on AWS.

An ABDTOPConsult report commissioned by the Dutch government concluded that the Netherlands has become ‘analog incapable’: there is no Plan B, no fallback servers, and the institutional knowledge to run processes without cloud has largely evaporated. The Algemene Rekenkamer found that 67% of the most important public cloud services had no risk assessment performed before adoption.

A legal conflict without resolution

The dependency creates more than operational risk. The US CLOUD Act (2018) requires American service providers to hand over data they control regardless of where it is stored. This directly conflicts with GDPR Article 48, which states that foreign court orders requiring data disclosure may only be recognized if based on an international agreement. The European Data Protection Board has concluded that service providers subject to EU law cannot legally base disclosure of personal data to the US on such requests. Complying with a US warrant violates European law; refusing a US warrant violates American law. No resolution mechanism exists. In testimony before the French Senate on June 10, 2025, Microsoft France’s director of public and legal affairs Anton Carniaux was asked if he could guarantee under oath that French citizen data would never be transmitted to US authorities without French authorization. His answer: “No, I cannot guarantee that.” A binding US court order could prevail. This means that European data stored on US cloud infrastructure is potentially accessible to American intelligence and law enforcement, regardless of what ‘sovereignty’ labels the cloud providers attach to their European data centers.

When trade conflicts meet digital infrastructure

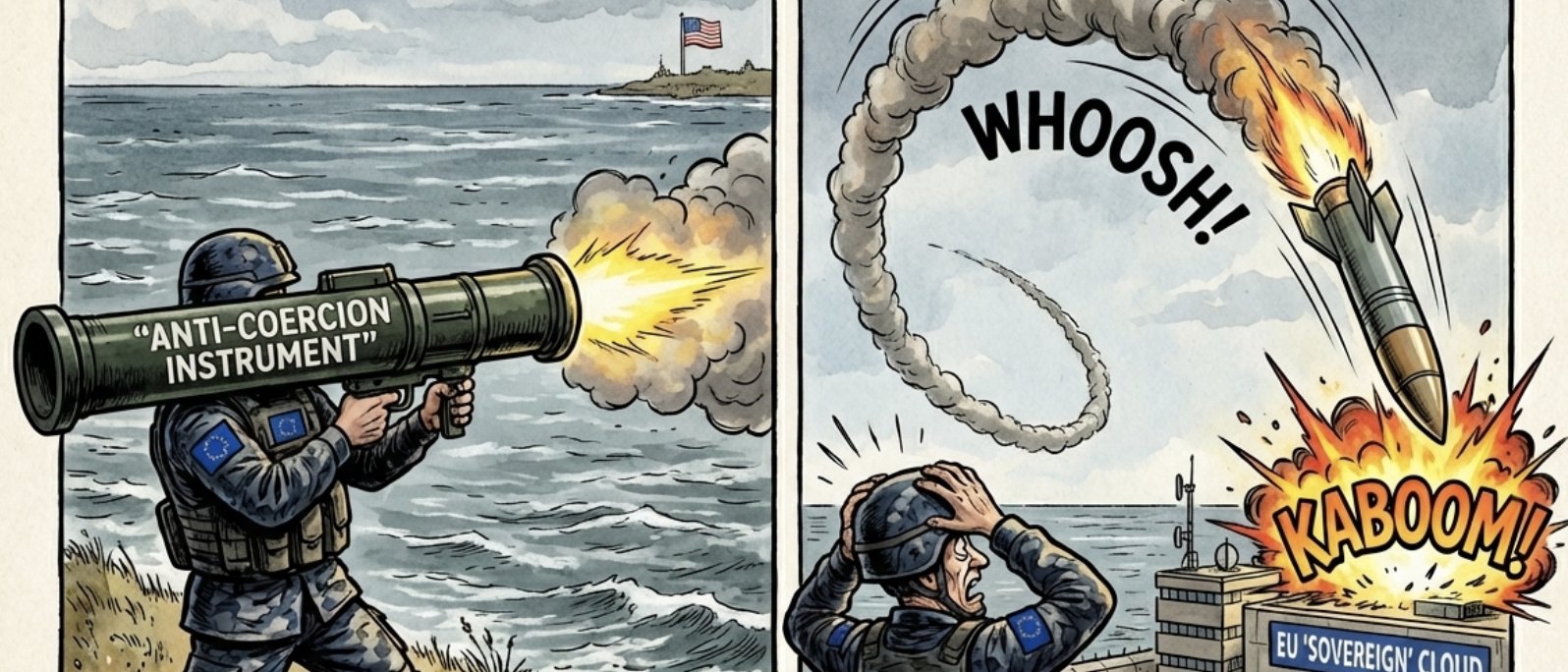

The current transatlantic tensions illustrate how quickly theoretical vulnerabilities can become practical concerns. The EU has a tool called the Anti-Coercion Instrument (nicknamed the ‘bazooka’), adopted in November 2023, which allows restricting trade in services, excluding companies from public procurement, and limiting market access when a third country attempts to pressure EU policy through economic coercion. Theoretically, this instrument could restrict US cloud providers’ access to the 500-million-consumer single market. But here’s the paradox: actually using it would cause massive disruption to European businesses and public services. The dependency itself limits Europe’s policy options. We have a precedent for what sudden withdrawal looks like. In 2022-2024, Microsoft terminated access to over 50 cloud products for Russian companies following sanctions. Microsoft had been used by 90% of corporate and state clients in Russia. Companies had limited time to export their data before cutoff.

What failure looks like

Even without geopolitical conflict, concentrated cloud infrastructure creates systemic risk. The CrowdStrike incident in July 2024 crashed 8.5 million Windows devices globally in a single morning, causing over $10 billion in damages. Delta Airlines alone lost $500 million. Over 5,000 flights were cancelled. AWS outages have repeatedly taken down major services including Prime Video, Snapchat, Reddit, WhatsApp, and Signal. Google Cloud failures cascaded to affect Spotify, Discord, and Twitch. These were technical failures, not deliberate actions. They demonstrate what happens when critical infrastructure is concentrated.

The European Parliament report on technological sovereignty calls for reducing reliance on foreign cloud providers while fostering European alternatives. The EU has designated 19 major tech providers as critical infrastructure under new regulations. Without decisive action, Europe risks what some have called becoming a ‘digital colony’.

Why European alternatives struggle

European cloud alternatives exist: OVHcloud, Deutsche Telekom’s sovereign cloud offerings, Scaleway, Hetzner, IONOS. But OVHcloud, Europe’s largest independent provider, holds only about 2% market share. The investment gap is significant: US hyperscalers invest approximately EUR 10 billion per quarter in European infrastructure. European providers collectively generate only EUR 9 billion in annual revenue. But the challenge goes deeper than investment. As Bert Hubert argues in a recent analysis, large cloud providers sell something far more valuable than computing power: they sell risk-free decisions. In corporate and government environments, an extremely important value is never getting blamed. If you choose AWS and something goes wrong, you can assign 100% of the blame to the vendor. If AWS suffers a day-long failure, everyone experiences that failure, which provides cover. It’s the same dynamic that used to be called ‘no one ever got fired for buying IBM’.

A European provider with EUR 10-100 million in annual revenue simply cannot offer this ‘blame absorption’ at scale. They don’t have the infrastructure to deal with customers making mistakes, the army of consultants ready to defend your choices, or the ecosystem of certifications that work on the job market. When European idealists talk about offering the most efficient, most secure services, they’re speaking a different language than the corporate decision-maker who needs to survive the next reorganization. GAIA-X, the Franco-German initiative launched in 2020 to create European cloud infrastructure, has been widely described as disappointing. It produced documents but few tangible results. Critics argue that allowing US hyperscalers to join undermined the initiative from within. The knowledge gap compounds the challenge. Brain drain is real: top US tech researcher salaries can reach $500,000 or more annually, while European academic salaries are significantly lower. The EU captures only a small fraction of global venture capital compared to the US. However, there’s now a new calculus emerging. As Hubert notes, European providers can increasingly offer something the hyperscalers cannot: protection against ‘getting blamed for going out of business after US sanctions’. The International Criminal Court recently switched from Microsoft to European open-source alternatives precisely for this reason. In a world where geopolitical reliability matters, sovereignty is becoming its own form of corporate comfort.

Why understanding this requires multiple disciplines

Digital sovereignty is not a purely technical problem. A legal expert might understand GDPR but not cloud architecture. A technologist might assess alternatives but miss the jurisdictional implications. A political scientist might analyze power dynamics but underestimate technical lock-in effects. An economist might calculate switching costs but not understand the regulatory landscape. And none of them might grasp the organizational dynamics that make ‘blame absorption’ a decisive factor in procurement decisions.

Addressing this challenge requires professionals who can think across technology, law, policy, economics, organizational behavior, and social impact simultaneously. It requires understanding how cloud architecture works, how data protection law applies, how trade instruments function, how market concentration affects bargaining power, how corporate decision-making actually operates, and how infrastructure choices shape democratic autonomy. These are not abstract questions. They determine whether a government can guarantee its citizens’ privacy, whether hospitals can function during a transatlantic dispute, whether unemployment benefits get paid when a trade war escalates.

Looking forward

Europe is beginning to take digital sovereignty seriously. The EU has designated major tech providers as critical infrastructure under new regulations. Several member states are investing in sovereign cloud capacity. AWS has launched a ‘European Sovereign Cloud‘ in response to these concerns, though questions remain about whether US-headquartered providers can truly offer sovereignty guarantees given the CLOUD Act. The conversation has shifted from ‘if’ to ‘how’. But building genuine digital autonomy will take years, substantial investment, and professionals who understand the full complexity of the challenge. It will require people who can bridge the gap between technical design and societal impact, between legal frameworks and engineering constraints, between geopolitical strategy and organizational reality.

If these questions interest you, and if you want to develop the interdisciplinary skills to address them, consider exploring the DIGISOC European Joint Master in Digital Society, Social Innovation and Global Citizenship. This programme, developed by the EURIDICE consortium of European universities, trains the next generation of professionals who can analyze and shape digital society from multiple perspectives, combining technical knowledge with insights from law, humanities, social sciences, and economics